I just wrote a short paper titled Dramatic Job Revisions Bust Structural Unemployment Myths. Here is the abridged version:

“When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?” – John Maynard Keynes

– The debate over structural unemployment that has taken place surrounding high levels of job openings and the Beveridge curve in 2010 needs to be reconsidered. Due to a pre-recession calibration of its birth/death model, the Bureau of Labor Statistics dramatically overestimated the number of job openings throughout 2010. It corrected the numbers for 2009 through 2010 in March 2011.

– On average, there were 172,000 fewer job openings per month in 2009 and 235,000 fewer job opening per month in 2010, reducing the job opening rate by an average of 0.18% over 2010 than had previously been reported. A quick and simple analysis shows that this BLS correction would have dropped estimates of increases in the NAIRU at the time from 1.3% to 1.0%.

– Since April 2010 when concerns about structural unemployment started to enter the debate, the Beveridge curve has almost entirely shifted leftward, with unemployment down roughly 1% and job openings up a meager 0.1%. Runaway unfilled job openings haven’t shown up in the data.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the number of job openings spiked in the summer of 2010. While this might normally be a cause for celebration, it actually worried a number of economists and policymakers. If an increase in the number of job openings co-exists with high unemployment, it means firms’ ability to find workers has decreased. If this signals that an economic model called a Beveridge curve has shifted outward, it means structural unemployment has increased and the ability of the economy to match workers and firms has decreased. In general, demand-based stimulative fiscal and monetary policy will do little to help the economy when it faces these kinds of problems.

That this increase in the number of job openings the BLS was reporting changed the nature of the debate on the job crisis is an understatement. The president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Narayana Kocherlakota, used the numbers to state that unemployment would be at 6.9% without structural problems and that “it is hard to see how the Fed can do much to cure this problem.” Former President Bill Clinton told NPR and the David Letterman Show that “first time new job postings are opening up twice as fast as job hires….because of skills mismatch….[Without these problems unemployment would drop from] 9.6 to 6.9,″ echoing Kocherlakota’s analysis. David Brooks used Kocherlakota’s analysis in a 2010 editorial about structural unemployment, noting, “One of the perversities of this recession is that as the unemployment rate has risen, the job vacancy rate has risen, too.”

A large debate broke out among economists, with one side saying that the rise in job openings showed deeper problems in the American workforce and another side saying that the rise in job openings was a natural part of a cyclical downturn and that we’d see circular motions in the Beveridge curve. Conferences were held, panels convened; Peter Diamond spent part of his Nobel Laureate lecture discussing these issues. Both sides took for granted that the 2010 job opening rates had increased to the extent that the BLS reported they had.

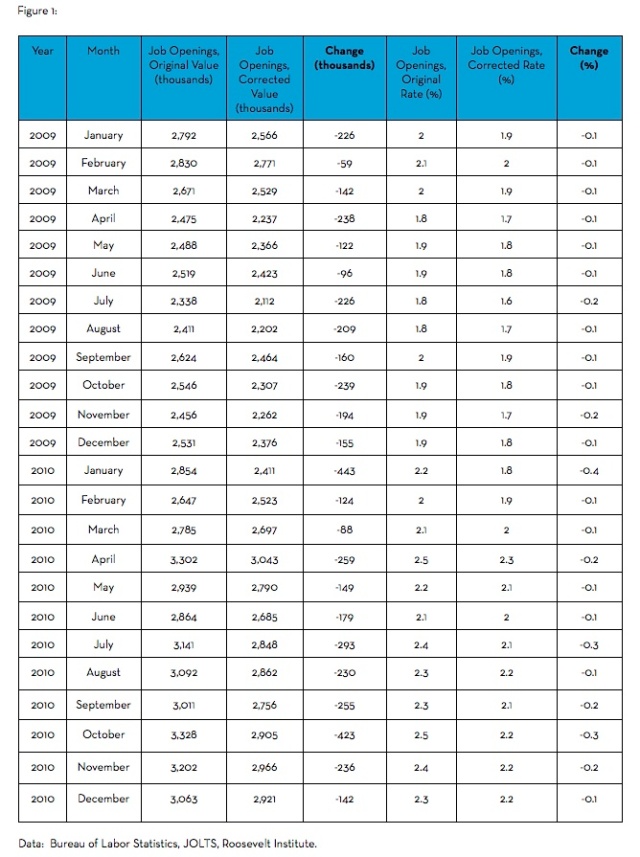

In March of 2011, the Bureau of Labor Statistics revised its numbers for job openings from 2006 through 2010, dramatically reducing the number of job openings for the last months of 2008 and the entirety of 2009 and 2010. The revisions are in Figure One below.

(Full revisions, 2009 revisions, 2010 revisions.)

On average, there were 172,000 fewer job openings per month in 2009 and 235,000 fewer job opening per month in 2010 than had previously been reported. This reduced the job opening rate by an average of 0.18% over 2010. The average number of job openings in the pre-correction data was over 3 million during 2010; in the new data, the number of job openings only reaches 3 million once. This is a massive shift downward from the previously reported number of job openings.

Why Did this Shift?

Why were the revisions so dramatic and entirely downward? As people from BLS explained, JOLTS samples from data in their sampling frame, and there’s a year lag between establishments entering their sample. As such, they can’t sample from businesses in their first year while they are outside their sampling frame. A lot of hiring and job activities happen in the first year, so it is important for BLS to estimate this figure.

In order to compensate for this, the BLS JOLTS team created a birth/death model (for births and deaths of business establishments) in 2009 to help gather numbers related to jobs. This model forecasts hires and separations of businesses in their first year. It was inserted into BLS numbers in 2009 and used values from 2000 to 2007 to populate the model. It then projected those values forward. Given that the 2000 to 2007 calibration didn’t feature a recession as deep as the one that occurred post-2008, this biased its birth-death model toward higher numbers.

So the birth model didn’t include data from the recession. The model wasn’t updated in 2010. In March 2011, it updated this birth/death model with additional data from the recession of 2008-2009 that then became available. Before it had used data through 2007 forecasted into the future, and now it uses data through 2009 forecasted into the future.

Now the birth model takes the recession into account. The difference is obviously dramatic, and when it went back and did a revision it drove down all the rates from 2009 and 2010. Since unemployment was much higher and business activity more depressed in 2008 and 2009 than in the seven years before, the previous projections forward were too optimistic. This is why the job opening rates were revised downward.

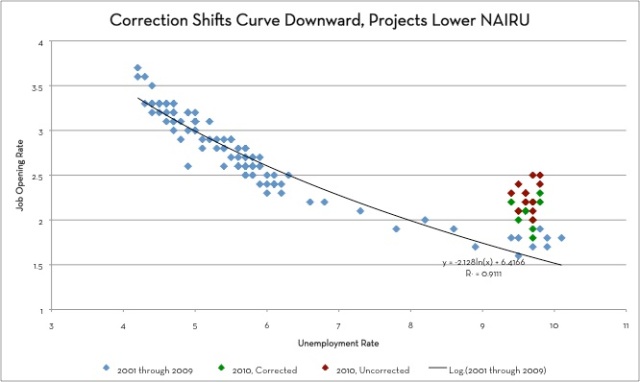

As Figure 2 shows, this has important implications for an economic model called a Beveridge curve, shifting the curve downward during the recession and subsequent period.

What Does This Downgrade Mean For Structural Unemployment?

In order to estimate how much this downward shift would change our estimates of an increase in structural unemployment, I created a quick and simple regression on the Beveridge curve using data from JOLTS for 2001 through 2009 (see Figure 3). For the year 2009, I used the average between the corrected and uncorrected data.

I then projected how far out the unemployment curve has moved for the values of the year 2010. To take an example, in October 2010 the unemployment rate was 9.7%. The uncorrected job opening rate was 2.5, which corresponds to an unemployment rate of 6.29%. The corrected job opening rate was 2.2, which corresponds to an unemployment rate of 7.25%. With the corrected job opening rate we see less of a shift of the unemployment curve.

The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco argues that “Credible estimates of the natural rate over these earlier periods suggest that it may have changed about half as much as the horizontal shift in the Beveridge curve.” Using this rule of thumb, I found that my estimate gives an increase in the NAIRU of 1.30% when I use uncorrected job openings, findings similar to other estimates, including the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, which estimates that this uptick is largely temporary. This leaves a lot of cyclical slack with unemployment at 9%.

With the corrected job openings data, we see the estimate of an increase in NAIRU drops to 1%, which means using the corrected numbers should drop the estimate of NAIRU 0.30%.

What has Happened Since Summer 2010?

Policymakers have worried that structural unemployment would stifle the recovery. The implication is that job openings would continue to rise while unemployment stayed high.

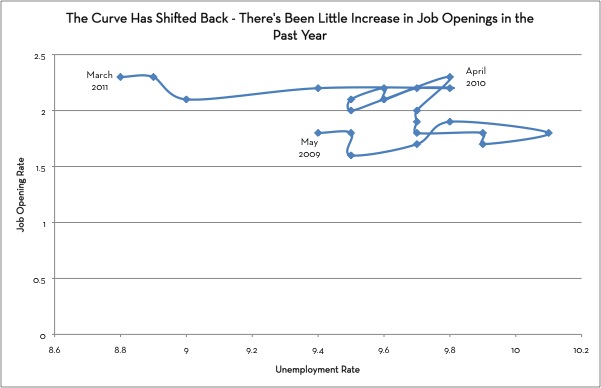

In both the corrected and uncorrected version of the job openings data, job openings peaked in April of 2010. What has happened to the curve since then? Figure 4 shows what has happened to the curve over the past two years (it uses corrected data).

There has been a straight decrease in the unemployment rate with virtually no increase in the job opening rate. The number of jobs available has remained flat and unemployment has fallen roughly one full percentage point. Those who were worried that any decrease in unemployment would happen alongside a runaway rise in the job opening rate should shift their concerns back toward low job growth.

The numbers guiding policymakers and experts are subject to revision, and job openings, a key component of any recovery, have turned out to be much lower than anyone had expected during 2010 when the debate over structural unemployment started.

Even before this, there was considerable evidence that there is tremendous slack in the economy and room for monetary and fiscal stimulus. With this correction, the story of an economy held in check by a weak labor force rather than weak jobs is harder to justify, and the argument for doing more is stronger.

Pingback: Spilled Beveridge - NYTimes.com

I’ve been in a lot of these economists’ seminars about which you speak (even been the presenter in some). We nerds, coddled in our ivory tower, debate why the rest of the labor force just isn’t suited for the economy. I almost feel disappointed that our big puzzle is actually not as big as we thought.

That said, your little Top Kill hasn’t totally plugged the leak. The Beveridge curve is really an equilibrium outcome, and there are multiple scenarios of “structural” or “cyclical” shocks that would be consistent. Suppose there is a “structural change” in which some technologies die out and others expand. In most of these search/matching models there’s a constant flow posting cost, so if firms know the workforce’s skills are not going to create productive matches, they won’t just keep open costly vacancies: the jobs aren’t posted and they don’t get filled. The observation, low expected match productivity causes fewer vacancies and matches, is the also same outcome in an aggregate demand shock, so this doesn’t tell you anything about whether it was an aggregate demand shock or a structural/variance shock.

You need one more measurement to disentangle this issue. On your side is the fact that employment has expanded fairly broadly across sectors. However, on the other hand, increased occupation/industry switching by unemployed and longer duration of unemployment suggests structural changes ( switchers always take longer to rematch).

Dave,

Good to see you here. How costly is a vacancy, really? Hall and Milgrom (2008) calculate that the daily cost of maintaining a vacancy is 0.43

days of pay (or about $66 per day), but I wonder if that cost has plummeted in this recession.

There’s indexes of search intensities people are trying to put together for job vacancies, which I’ll blog about tomorrow (see WSJ here for now), and far as I understand those numbers employers are trying less hard to fill vacancies. Would the intensity go up or down if your theory that employers are rationing vacancies on their rational expectations that workers aren’t there for the vacancies is correct?

Side note: did you read Bob Hall’s recent paper about the zero-bound spiking unemployment in a Diamond-Mortensen-Pissarides like model, where I got the above numbers (a model that is in full equilibrium, boom)? I have a feeling that’s the next big thing that will replace the awkward structural games – what are you hearing?

Pingback: David Brooks On High “Structural” Unemployment | Rortybomb

“When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”

John Quiggin wrote a bleg some time ago asking for a source for that Keynes quote. I don’t suppose you have one? It seems to be apocryphal, if that’s the word I’m looking for.

Pingback: FT Alphaville » Further further reading

On vacancy costs: True, they’re probably actually cheap. It’s a required piece mathematically in these models, but I guess I don’t know any other measurements to say they’re actually significant.

The idea of search intensity from the employer’s side is kind of interesting. The reason that we don’t generally have it is because in the models vacancies adjust continuously to adjust the probability of filling it so that

vacancy cost = Pr[fill vacancy] x Expected return from match

holds. Then, to match to the data we just count (a proxy of) the number of vacancies, but if there’s some variation in quality/intensity of search, this is a big misuse of data for our models. A potentially really interesting thing to explore, actually!

My own side note: Lots of models have workers’ search intensity and the odd thing is that a lot of the predictions here (intensity should go up as duration extends and benefits dry up) don’t hold up. In an NBER EF&G paper, Krueger interviewed a bunch of unemployed guys in this recession and found longer unemployed reduce their intensity.

Your side note: Not only did I see the paper, he presented it at the MPLS Fed just before taking it to the big AEA meetings. It’s a nice piece of work, but there’s lots of (his words) “heroic assumptions” to make the transmissions mechanism from interest rates to employment. It’s kind of a neat idea though: models have a few “jump variables” that are able to move so that markets clear, while stocks move slowly. If the price (interest rate) is stuck, other stuff must move lots.

Mike, is there any attempt to adjust for the quality of job openings when ascertaining whether or not there is structural unemployment? It seems to me that it doesn’t have to be a skills mismatch–it could be that employers want to pay too little to get people to take the jobs. I am always hearing anecdotal evidence in the NY Times that employers can’t find the skilled machinists they need, but then in paragraph 12 of the story you find that the employer is offering $12/hour. The problem is demand–employers are willing to hire if they can get somebody really cheaply, but they aren’t willing to raise the offer to a level that would fill the job.

As far as I remember it, from BLS: “A job opening requires that 1) a specific position exists, 2) work could start within 30 days, and 3) the employer is actively recruiting from outside of the establishment to fill the position. Included are full-time, part-time, permanent, temporary, and short-term openings. Active recruiting means that the establishment is engaged in current efforts to fill the opening, such as advertising in newspapers or on the Internet, posting help-wanted signs, accepting applications, or using similar methods.”

So from #3, a permanent full-time job with benefits is the same count as a short-term minimum wage temporary hire. The job openings number is a very thin description as far as numbers go. You could look at it alongside hours worked and wage compensation to get a larger sense of what is moving.

““When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”

John Quiggin wrote a bleg some time ago asking for a source for that Keynes quote. I don’t suppose you have one? It seems to be apocryphal, if that’s the word I’m looking for.”

It’s attributed to Keynes in: Lost Prophets: An Insider’s History of the Modern Economists (1994) by Alfred L. Malabre, p. 220

The Keynes quote I was after was “The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent”, which I concluded was apocryphal, though Keynes clearly states the idea it expresses

Thank you for your very important contribution to the debate. You will have noticed that it has received the attention it deserves.

I have two thoughts.

First (and tiresome not new and all that) Kocherlakota, Clinton and Brooks ignored the well known counterclockwise cycles above the Beveridge curve. As you argue, drawing a horizontal line implies always asserting that there is very high structural unemployment early in a recovery. I think this is about as big an issue as the correction which is the point of the paper and the post. When explaining things to non-sepcialists you might want to review settled issues and previously known problems with Kocherlakota’s calculations.

Second, the BLS could do better. I had no idea that they ignore firms for a year. I can only guess they choose this sampling frame because they are interested in yearly salaries or something. I think we must respond to their poor performance by raising their budget.

Given the importance of JOLTS it seems to me that the BLS should have two samples picked from different samplign frames. It would be better to sample firms as soon as their existence is known (just founded firms will have lots of vacancies). There would still be need for a birth/death model, but it wouldn’t imply such huge adjustments or, well nonsensical numbers such as those you discuss. Am I missing some problem with the two frames one for vacancies and one for salaries (or whatever) approach ? How much would it cost ? I don’t know.

I don’t know anything about the birth death model, but, as far as I can understand, the BLS assumed that firms were being founded at the same rate since 2007 as they were 2000 through 2007. That would be insane. I understand how the need to calculate estimates according to rules can (and should) force BLS employees to do things which seem crazy ex post (we sure don’t want them free to tell us numbers based on their hunches) but this could have been explained more clearly. Well I’m sure it is explained somewhere and the problem is that economists don’t want to look at how the data are estimated, because it is boring and depressing. But shame on us.

If the BLS did what I guess they did (OK shame in particular on me for not looking it up and wasting pixels) then surely it can do better. Instead of a few years of data it could look at the ratio of new firms to existing firms as a function of a time trend and employment growth in year old firms (a number which they calculate and which is available monthly).

On job openings and employer recruiting.

I have been in firms that have laid off a large number of people and have interviewed at firms that have been hiring. I will say that hiring intensity may be inversely correlated to the need to fill the job.

To whit, firms that have had massive layoffs post job openings to help employees keep the faith. The problems with morale after layoffs are both because the employees need to do extra work, and because of a sense of more doom ahead. Employers post job openings for Moses (qualification: must walk on water) and then run intense recruiting efforts, often with commission based recruiters that do not get paid unless the job is filled. The employees are entertained with a constant flow of higher qualified potential employees that have been desperate for work. This has the effect of focusing the attention of those with jobs, lest they be replaced with Moses. Then again, if you do find Moses, there is the potential for another fired employee to cheer up the employer, parting the waters for Moses.

Often firms listed jobs just to keep the employees from fearing that funding would run out, and lose everyone to instant job hunting. This is especially prevalent in small companies.

Another aspect is writing qualifications directly suited to H1Bs, so that only the H1B can satisfy the job, and the said H1B can take that job with him to the Far East facilitating offshoring.

Lies, damned lies, statistics. (oft attributed to many much more illustrious than I).

Pingback: Structural Unemployment