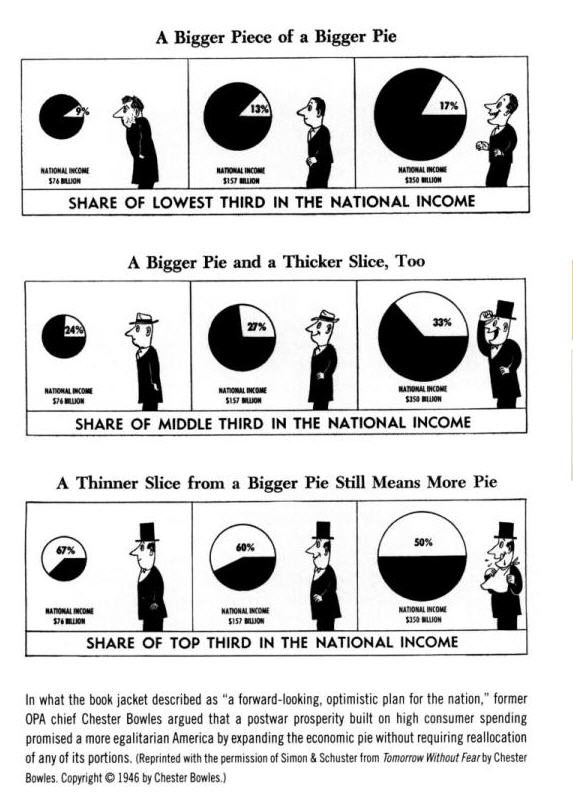

Isn’t this chart from 1946 fantastic? Click to see it full sized.

(from A Consumer’s Republic) “A thinner slice from a bigger pie still means more pie.” We don’t even talk in terms like this anymore. I wonder if a more equal distribution of wealth makes growth more stable, and get nothing in terms of economic theory. And even in public policy talking in terms like this seems taboo, and the media sphere is even worse given the outrage on Obama’s “spreading the wealth” line.

I’m on a huge deadline at work this week, so of course there’s a lot of blog movement on one of my favorite topics – the move from the economy, labor arrangements and income distributions of the 1950s-1970s (which I’ll call Fordist here) to the one of the 1980s-now (which I’ll refer to as Post-Fordist).

Brink Lindsey has an excellent post at Reason critiquing Paul Krugman’s account of the story.

By contrast, Krugman sees the rise of inequality as a consequence of economic regress—in particular, the abandonment of well-designed economic institutions and healthy social norms that promoted widely shared prosperity. Such an assessment leads to the conclusion that we ought to revive the institutions and norms of Paul Krugman’s boyhood, in broad spirit if not in every detail.

There is good evidence that changes in economic policies and social norms have indeed contributed to a widening of the income distribution since the 1970s. But Krugman and other practitioners of nostalgianomics are presenting a highly selective account of what the relevant policies and norms were and how they changed.

The Treaty of Detroit was built on extensive cartelization of markets, limiting competition to favor producers over consumers. The restrictions on competition were buttressed by racial prejudice, sexual discrimination, and postwar conformism, which combined to limit the choices available to workers and potential workers alike. Those illiberal social norms were finally swept aside in the cultural tumults of the 1960s and ’70s. And then, in the 1970s and ’80s, restraints on competition were substantially reduced as well, to the applause of economists across the ideological spectrum. At least until now.

Jim Manzi and Ryan Avent have great followups. If this is of any interest to you, I’d recommend reading all three closely. I could write about this for hours but sadly can’t, so I want to add three quick puzzle pieces to the table.

The Cold War

“Our houses are all on one level, like our class structure.”

House Beautiful (Popular 1950s Magazine)

“an American working man can own his own comfortable home and a car and send his children to well-equipped elementary and high schools and to colleges as well. They [the Soviets] fail to realize that he is not the downtrodden, impoverished vassal of whom Karl Marx wrote. He is a self-sustaining, thriving individual, living in dignity and in freedom.”

President Eisenhower, 1960

What would poor Eisenhower think now? One thing that is missing in the narratives is the Cold War as a reason for ensuring a healthy middle-class. There’s a mix of motives here, but a genuine belief that we were not only more free but also providing a more equitable lifestyle than the Communists were was a major ideological selling point in the cultural Cold War.

Check out this film for students, Despotism (1946). It is produced by Encyclopedia Britannica and it explains the difference between Democracy and Despotism. In the video, he draws a line with Democracy on one end and Despotism on the other end. Power and Respect both have their lines, with more Respect (for everyone) and Power less concentrated associated with democracy. It’s also cheesy wonderful.

I highly encourage you to watch between 4m20s and 6m30s, where he talks about Economic Distribution – where balanced is associated with democracy, and slanted (ie – inequality) is associated with despotism. They draw an explicit comparison between having a strong middle class, progressive taxation and implicitly the right to unions (protecting people from dependency on large concentrated hirers) and having a strong democracy, which given this context also mean being able to fight off the communists.

So in some sense a strong middle-class is a byproduct of the contingent circumstances of having to convince people, both home and abroad, that the Americans have more to offer than the Soviets. A lot of the strong social democracy of the period is also affiliated with this – our great public colleges, for instance, was born of the moment where we were worried that the Soviets were outpacing us on technological production. We don’t have the Cold War to worry about anymore, so as such a lot of the direct rationalization for a government to push the distribution in this manner has disappeared.

(Indeed, I wonder if part of the reason the Culture Wars hang less heavy on us is a result of the War on Terror. Now locking up homosexuals, denying women autonomy over their bodies and embracing an unwavering faith in a metanarrative is the stuff our enemies do – our tolerance and skepticism is something that separates Us from Them. I’m not sure if this explains a lot, but I did note that the one move against it, an argument made by Dinesh D’Souza in “The Enemy At Home” that culturally conservative Americans in the heartland should feel a solidarity with culturally conservative Muslims in the Middle East in hating the dreaded liberal cosmopolitan was met with dead silence, dead silence in a space that even makes Mark Levin and Sean Hannity into bestsellers.)

Deregulation as Progressive Culture

Indeed, the relevant changes in social norms were led by movements associated with the left. The women’s movement led the assault on sex discrimination. The civil rights campaigns of the 1950s and ’60s inspired more enlightened attitudes about race and ethnicity, with results such as the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, a law spearheaded by a young Sen. Edward Kennedy (D-Mass.). And then there was the counterculture of the 1960s, whose influence spread throughout American society in the Me Decade that followed. It upended the social ethic of group-minded solidarity and conformity with a stampede of unbridled individualism and self-assertion. With the general relaxation of inhibitions, talented and ambitious people felt less restrained from seeking top dollar in the marketplace. Yippies and yuppies were two sides of the same coin.

Lindsey puts a lot of weight on this. There’s a narrative where the deregulation of the economy reflect a progressive movement for equality among races and genders. The Union of the 1960s is akin to another form of Jim Crow – something where a set of Americans are privileged over another and excluding those outside is the main priority. As such, the deregulation of the 1980s is the last step of a progressive movement that began with shredding restrictive social norms against women and men.

It’s a nice narrative, but I tend to read it the opposite way – deregulation takes place in a space where government intervention was viewed as protecting minorities instead of majorities. Reagan policies were less about opening doors for minorities, but instead about forcing “welfare queens” to go and get a job. And the type of market rationality that came with it was less about the liberal aspects of the market – markets ensures growth for all – but instead a deep conservatism of the markets – the market ensures that we are separating the winners from the losers, the good from the wicked, the productive from the lazy.

I see this with a lot of the roadblocks liberalitarians hit with social safety nets. Let’s say free trade is like this. There are 100 people in your country, and you are going to do something that causes 10 people to lose $5, and the other 90 are going to each make $1. You should do it! It’s a net $40 increase for the country.

What about those ten people though? That’s really unfair. Well the liberal response, the one in keeping with the tone of the articles, is that we can simply take $51 out of the new $90 and ‘give it’ to the 10 people, in the form of job training, unemployment insurance, whatever. Still optimal for everyone.

But what if the point of this exercise isn’t to make a net $40, but instead to expose those 10 people? To use it as a warning to discipline people 11-20 that they better not screw up? To force them to be more respectful of the power structures in place? There’s a reason that, even in 2009, someone going on TV and calling those who are underwater on their mortgage “losers” can have such resonance, and I believe it is because there’s a large segment of the country that views markets less about growth for all but about punishment for few. The people who are “getting away with something” are forced to go hungry, while those who work and are productive are going to get better off.

I think there’s a change in the landscape right now, both generationally and also as a result of the Financial Crisis, so this analysis will probably not be useful going forward. And this is a small sketch of a larger argument, but I think it explains a big chunk of the “What’s the Matter With Kansas?” question.

Cognition

Whether or not inequality is the result of higher returns to cognitive skills or education is fiercely debated by labor economists. I’d take a quick look at this chart:

If it was really just about smart people getting rewarded more, why is all the reward in the top 1%? To whatever extent that story is true, there are other things going on as well. I’ll probably post more about this later when I have free time, but these are three points I find interesting and wanted to contribute right away.

“If it was really just about smart people getting rewarded more, why is all the reward in the top 1%?”

I trust you are familiar with the dynamics of compensation to sports players, actors, musicians, etc. – the so-called super-star effect?

It strikes me as eminently plausible that the higher the inequality, the more ability, as opposed to being a warm body, is being rewarded. Whether or not that is “good” for society is an entirely separate question.

Definitely. I find the effect where, as a result of increasing communication technology, it is the same ‘cost’ to provide the ability to the second-best entertainment versus the first-best entertainment, there will be a pooling effect at the best effect. Though it is important to realize this is different than cognitive abilities or returns to education. That’s going to be part of it.

However it’s important to realize that these agents are still employees – someone writes Michael Jordan his check. Who is that? And what’s going on with them? I’m curious to see that explored more. I’ve heard research, though I am not that familiar with a lot of it, that if you take out New York and DC a big chunk of inequality disappears. I should read that more and post on it….

This is my favorite post ever, in a long personal and blog-sharing history that spans many posts and post equivalents.

I cannot tell you how many times (albeit often in response to me asking the question) undergrad business students tell me that they have never heard or seen the word “inequality” used in the course of their education. It’s not that they look at inequality and rationalize it or argue that it’s beneficial – it simply does not exist. The concept is like a word in a foreign language which has no direct equivalent in whatever language they speak.

There seem to be two culprits: the effort of economics as a discipline to establish itself as a “hard” science and not a social one (thus encouraging purges of anything that feels even a little like Gay Sociology Bullshit) and the 1984 Orange County republicanism that swept the suburbs over the last two+ decades.

It’s dangerous to idealize the way People Used to Be, but part of me is quite convinced that 50 or 60 years ago the concept of inequality would at least enter the discussion, even if treated patronizingly. Today it’s less a question of not wanting to discuss it and more the idea of not being able comprehend WHY such a concept would have a place in a discussion about macroeconomics. Inequality is growing because poor people are lazy and don’t want to work, thus it is not the province of macroeconomists to police or attempt to police.

Reagan policies were less about opening doors for minorities, but instead about forcing “welfare queens” to go and get a job.

Actually, it was much more vicious than that – because the same party was also opposing the “interference in the market” aimed at making it even *possible* for those minorities to get a job, and defunding the agencies tasked with enforcing the antidiscrimination laws they couldn’t actually repeal.

Allow Jim Crow to reappear in slightly subtler forms, then blame its victims for not having jobs and attribute it to their inherent failures. And people *wonder* why this party didn’t take the high road on Sotomayor?

Pingback: interfluidity » Rooseveltian Reflections

That Despotism video is a wonderful find. It seems like we’ve learned the wrong lesson from the Cold War and concluded that it’s the equality, or “socialism,” that is the problem and not the concentration of power at the top. We have forgotten that equality and democracy could work hand in hand. (Though they certainly don’t necessarily do, as China certainly proves.)

I fully concur.

FIRST Reagan acelerated the view that blue collar was something to hate. Skilled labor was not worth good wages and was causing the problems in the economy. He broke the air traffic controllers union and set off a wave of union hating. SECOND The military became a more sophisticated place ( Reagan increased computer use to beat Russia), and the country became more technical. RESULT Our country crapped on it’s young men. Now there were declining aprentice programs. You could not get into the army and turn around a troubled youth. You need a diploma to get into the army not a ged. We adressed girls and they have soccer and are way more sucessful now than our young men. Laura Bush tryed to speak to the issue of our young men and that went nowhere. SO WHAT DID THE RICH DO They decided we needed illegals to fill out the workforce told all levels of law enforcement to stand down. Now illegals have grown into every job not just the farm jobs of the past, because no self respecting young white american son would dare be blue collar IF YOU DIDN’T HAVE 12 MILLION ILLEGALS BUILDING HOUSES YOU WOULD NOT HAVE A HOUSING BUBLE NO MATTER WHAT THE FINANCIAL AND POLITICAL SENTIMENTS WERE. IT IS A RACIAL ISSUE, A CLASS ISSUE, AND A CORRUPTION ISSUE. ALL ECONOMIC POLICY RHETORIC IS JUST AN ATTEMPT TO REDEFINE THESE ISSUES.. LABOR VERSUS MANAGEMENT DEFINES ALL OF THE WORLDS HISTORY.

Why look at the top 1%? Why not at the top 0.1%? You’ll find all the lift there.

And if you look to see what these people do, it’s all Finance.

I will not be surprised to see the Obama administration throw doctors and engineers under the bus while saving the bankers, and be cheered on by Progressives the whole way.

As to there being no economic theory with respect to the relation between more equal income distribution and sustainable economic growth, might one go back to Ricardo? The real distributable surplus product is the total product minus that part used up in the process of its production. And it is distributed, as a conceptual reduction, between wages and profits, in inverse proportion. (I’m ignoring “land” rents, to simplify, but a) they are only activated within some system of production and b) ideally, they ought to be taxed away.) In principle, there is some “sweet spot” in the distribution between profits and wages, which a) provides sufficient returns on capital investment to replace and improve capital stocks and b) provides sufficient wages to absorb output through adequate effective demand. However, given underlying technical change, that spot is a moving target and must be discovered in process. But the fact remains that the distribution of income affects both the composition and level of real effective aggregate demand. And it is at once the cost pressure of wages and the sensed presence of adequate wage-based demand that incentivizes productivity improving real capital investment. (Wealthy individuals can’t be an adequate basis of demand, since, though any given individual might sell or borrow against their capital stocks, if all such do so, they crash their value. Though nowadays, in the U.S., consumption demand is heavily dependent on wealthier consumers, which inflates the prices of status and positional goods, Gucci and Harvard, but doesn’t do much to spur productive investment in increased, cost-reduced output. Note that there is a crucial difference between increasing profits through shifting the ratio of distribution between wages and profits and increasing profits through productivity-enhancing, cost-reducing investment). Hence a high skew toward profits accruing toward the owners of capital and a lowered distribution toward wages and salaries results in a decline in incentives toward real productive investment and thus a tendency toward inadequate demand and lowered growth or stagnation.

Appealing to libertarian and rightist commentators is, er, a bit rich. It’s true that under the post-New Deal arrangements various regulations structured productive surpluses and quasi-rents, which unionized workers, who also affected more general wage rates, could then participate in, while the whole point of the Bretton Woods arrangement was to encourage international trade in goods, while discouraging free flows of financial capital, and permitting national autonomies in appropriate fiscal, monetary and regulatory policies. But claiming that it’s demise was due to increased “competition”, which therefore increased efficiency and economic growth is counterfactual. To the contrary, the neo-liberal era, now in penultimate crisis, involved increasing consolidation of oligoploistic market and political power on an international scale and increased financialization of the real economy, skewing income distribution upwards toward those who own and control increasingly concentrated capital. Disguising such fundamental, secular economic structural shifts behind rhetoric about increased freedom and identity politics is a revisionary forgery of the actual dynamics and motives by which such social changes were brought about, and a perpetuation of the reactionary con-game.